But while there are many topics that fall under the huge umbrella of coffee extraction, there are a few key principles that can help coffee professionals and coffee lovers more clearly understand the process of coffee brewing.

What is Coffee Extraction?

Coffee extraction is the process of water pulling soluble materials from coffee grounds, which creates a drinkable coffee beverage. There are a few different materials, or compounds, that can be extracted from the coffee grounds. And each of these compounds has specific characteristics that affect the way a coffee tastes.

To get a better understanding of how to apply the theory of coffee extraction to coffee brewing, we spoke with Ben Put, five-time Canadian Barista Champion and Urnex Ambassador.

Ben likes to think of the concept of extraction as energy. In any brew method, for whole coffee beans to be transformed into drinkable coffee, they must undergo different types of energy inputs from different sources. The first source is the coffee roaster, who adds heat to green coffee during the roasting process. The more heat that is applied in roasting (as with a dark coffee roast), the more energy that is transferred to the coffee.

The second source of energy comes from variables the barista controls. While there are six essential elements of brewing that the barista can leverage, Ben believes that two variables in particular have far and away the most impact on extraction and flavor. And without dialing in these variables, it’s nearly impossible to make a coffee or espresso taste good.

Coffee-to-Water Ratio

In Ben’s energy analogy, water is the most important power source a barista has in his or her toolbox. Considered a universal solvent, water easily dissolves material and flavor from coffee by carrying heat through the grounds. The amount of water used in brewing is the first step in determining how much energy to add – in other words, at what level to extract the coffee.

When Ben first receives a coffee, he’ll brew it at a range he knows in general can produce tasty flavors. For espresso, he starts with a 2:1 brew ratio – so to produce 40 grams of liquid espresso, he’ll begin with a 20 gram dose of ground coffee. For filter coffee, he’ll begin with 60 grams of coffee per liter of water for a 16.6:1 ratio.

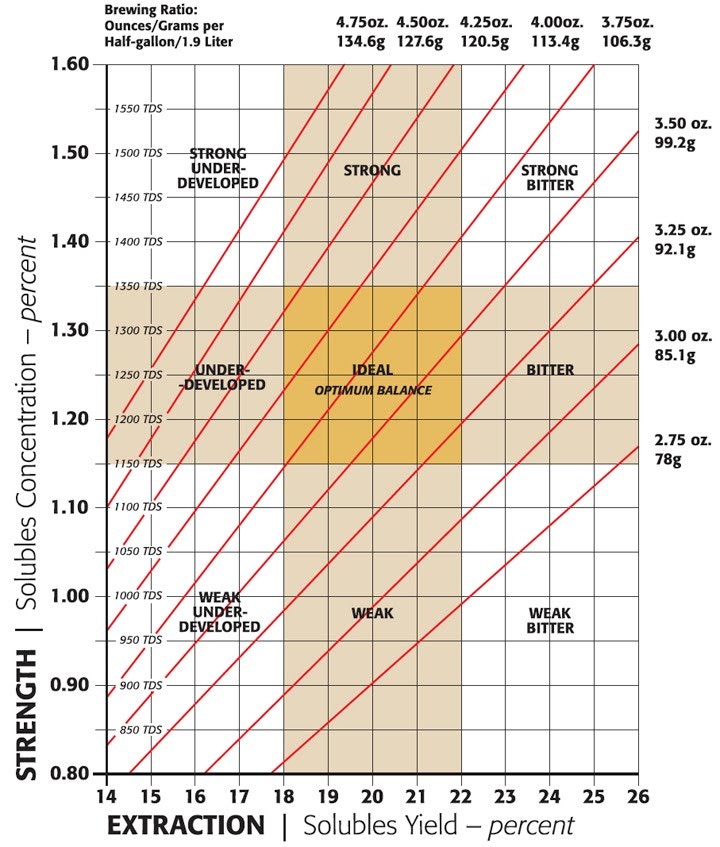

An important but tricky idea to understand is that extraction percentage is closely correlated to strength of a coffee, but they are not the same measurement. Strength is the amount of coffee material in the cup compared to the amount of water, while extraction relates to the percentage of coffee grounds dissolved into the water. As Ben explained it, “A good extraction percentage creates flavors, and a good strength creates intensity.”

Recognizing and tasting the differences between extraction and strength can be difficult as well. With extraction levels, the flavors from under- and over-extracted coffees have unique kinds of unpleasant flavors. Because acids in a coffee extract more readily than other compounds, a coffee that is under-extracted will taste sour, like a lemon. Other compounds in a coffee are presented later in the brewing process. But if the coffee becomes over-extracted, the flavors turn bitter or astringent. However, all coffee contains some level of bitterness from the caffeine, which naturally balances out the flavors in a coffee.

Determining the level of strength is a bit more intuitive: a coffee drink that used too much water in the brewing process is considered weak, which has a papery, dry or flat taste. A coffee that used too little water is considered strong, which has an ashy taste.

Grind Size

Back to Ben’s energy analogy: the finer the grind size, the more energy that is required from the grinder. So when working with a lighter roast, a barista will need to grind the coffee finer compared to a darker roast to achieve the right amount of total energy.

Because there is no standardized settings on coffee grinders, using a simple flow rate formula is an effective measure the fineness of grind. For instance, if it takes a total of 20 seconds to pull a 40 gram shot of espresso, you’ll have 2 grams of liquid espresso per second.

In measuring flow rate, there are two related variables that a barista can evaluate: grind size and contact time. By making the grind size finer, a barista is increasing the surface area of coffee particles, which will slow the shot down. This will increase the time the water flows through the coffee grounds, or contact time. Inversely, a coarser grind size will decrease a coffee’s contact time. Changing these variables in either direction can have a huge impact on flavor profiles of a coffee.

Here are five tips to elevate your coffee grinder skills.

Numbers vs. Taste

Beginning with brew ratio, Ben will start at a very low ratio of 33 percent, or a 3:1 ratio (eg: a 20 gram dose of ground coffee to yield a 60 gram shot of espresso). You’d expect that such a low ratio would produce either a weak espresso (the increased amount of water to reach 60 grams of liquid espresso could dilute the beverage) or an over-extracted one (the increased time to reach 60 grams of liquid espresso means increased contact time between the water and grounds, which could extract more of the bitter compounds in the coffee). But Ben will have his baristas make the shot smaller in small increments to taste the effect, and collectively they’ll choose their preferred brew ratio.

Following brew ratio, Ben will lead a similar test with grind size. He starts with a grinder setting in which the machine will produce a relatively coarse grind size in order to pull a relatively fast shot (2 grams per second). He’ll have his team make gradual adjustments to the grind size to slow the shot down until a shot of espresso reaches a speed of 1 gram per second.

Ben is a believer in using both mathematical measurements and more subjective judgements in taste. The numbers, and more advanced tools to measure them, allow a barista to quantify a coffee beverage precisely and accurately, which allows them to communicate details about a coffee across a café or large distances. But using both measurements and taste can allow a barista to learn about the flavor profiles of an induvial coffee, and to recreate those flavors time and again.

Ideal Extraction: Is There Such a Thing?

But will this be the ideal extraction range in the future? Maybe not. Ideal extraction percentage will always depend on the coffee a barista is brewing with. But there’s a sizable faction of coffee professionals that prefers a higher extraction percentage, generally between 20 and 22 percent or higher.

Ben says that these baristas might be onto something. Ben believes that as grinder technology advances, baristas will be able to more accurately extract higher percentages from of a coffee. This is because modern coffee grinders are not perfectly precise in producing identically-sized particles, so those particles are extracting at different levels. This makes knowing when to stop brewing a near-impossible judgement call for a barista.

Ben believes that as grinders become more precise, brewed coffee will become better.

“The better grinder technology gets, the closer to that final extraction level you can bring to the entire coffee,” Ben said. “That’s why people are advocating for higher extraction percentages now. All the coffee is moving together at a better rate, and that allows you to hit a higher extraction point. If everything was more even, you could brew better, more intense coffees with less physical coffee.”

Taking this idea further, Ben thinks that specialty coffee operations will begin to roast based on the grinder they’ll use to brew. Different grinders have different abilities to reach certain extraction levels. For example, a lower-quality grinder might only grind particles at size in which the brewing taste good at 19%, so the roast would need to work with a coffee at 19 percent extraction or less. But a top-of-the-line grinder, like a Mahlkonig EK43, can reach extraction levels of 23 percent and still taste good, so the coffee roast should be adjusted accordingly.

Specialty coffee is far from the only industry affected by advancing technology, but it’s a shining example of a product being transformed for good. We’ve come a long way from approximating our doses or determining extraction levels based solely on our palates. A combination of improvements in technology and deeper understanding of extraction will undoubtedly guide coffee professionals in the pursuit of better tasting coffee.

For more coffee theory, find out what makes an excellent espresso.